Aromaticitate: Diferență între versiuni

m →Teoria orbitalilor: m |

m →Teoria sextetului: reg huckel |

||

| Linia 33: | Linia 33: | ||

Armstrong anticipează astfel cel puţin 4 concepte moderne.Primul este afinitatea de fapt electronul de mai târziu descoperit de [[J. J. Thomson]].Al doilea concept este descrierea substituţiei electrofile prin intermediarul de tip Wheland (ion benzenoniu)(concept 3) , proces ce are loc cu distrugerea sistemului conjugat al inelului aromatic (al 4-lea concept).El introduce simbolul C centrat în mijlocul inelului interior , anticipând astfel notarea [[Eric Clar]].Prin aceasta se anticipează principiile mecanicii cuantice , de vreme ce recunoaşte că afinităţile(electronii) au aceeeaşi orientare, nu sunt punctiforme la nivel de atom, au o distribuţie uniformă ce poate fi alterată prin introducerea uneo substituenţi pe nucleul aromatic. |

Armstrong anticipează astfel cel puţin 4 concepte moderne.Primul este afinitatea de fapt electronul de mai târziu descoperit de [[J. J. Thomson]].Al doilea concept este descrierea substituţiei electrofile prin intermediarul de tip Wheland (ion benzenoniu)(concept 3) , proces ce are loc cu distrugerea sistemului conjugat al inelului aromatic (al 4-lea concept).El introduce simbolul C centrat în mijlocul inelului interior , anticipând astfel notarea [[Eric Clar]].Prin aceasta se anticipează principiile mecanicii cuantice , de vreme ce recunoaşte că afinităţile(electronii) au aceeeaşi orientare, nu sunt punctiforme la nivel de atom, au o distribuţie uniformă ce poate fi alterată prin introducerea uneo substituenţi pe nucleul aromatic. |

||

The [[quantum mechanical]] origins of this stability, or aromaticity, were first modelled by [[Erich Huckel|Hückel]] in 1931. He was the first to separate the bonding electrons into sigma and pi electrons. |

|||

== Condiţii de apariţie a stării aromatice == |

|||

Prin intermediul mecanicii cuantice[[Erich Huckel|Hückel]] explică stabilitatea , caracterul aromatic, separînd pentru prima dată electronii de legătură în electroni sigma şi electroni pi. |

|||

=== Regula HückelText de titlu === |

|||

[[Image:Benzol.svg|100px|thumb|right|[[Benzene]], the most widely recognized aromatic compound with six (4n + 2, n = 1) delocalized electrons.]] |

|||

In [[organic chemistry]], ''''s rule''' estimates whether a [[planar]] ring [[molecule]] will have [[aromatic]] properties. The quantum mechanical basis for its formulation was first worked out by [[physical chemistry|physical chemist]] [[Erich Hückel]] in 1931.<ref>{{citation | last = Hückel | first = Erich | authorlink = Erich Hückel | title = Quantentheoretische Beiträge zum Benzolproblem I. Die Elektronenkonfiguration des Benzols und verwandter Verbindungen | journal = Z. Phys. | year = 1931 | volume = 70 | issue = 3/4 | pages = 204–86 | doi = 10.1007/BF01339530}}. {{citation | last = Hückel | first = Erich | authorlink = Erich Hückel | title = Quanstentheoretische Beiträge zum Benzolproblem II. Quantentheorie der induzierten Polaritäten | journal = Z. Phys. | year = 1931 | volume = 72 | issue = 5/6 | pages = 310–37 | doi = 10.1007/BF01341953}}. {{citation | last = Hückel | first = Erich | authorlink = Erich Hückel | title = Quantentheoretische Beiträge zum Problem der aromatischen und ungesättigten Verbindungen. III | journal = Z. Phys. | year = 1932 | volume = 76 | issue = 9/10 | pages = 628–48 | doi = 10.1007/BF01341936}}.</ref><ref>{{citation | last = Hückel | first = E. | authorlink = Erich Hückel | title = Grundzüge der Theorie ungesättiger und aromatischer Verbindungen | publisher = Verlag Chem | location = Berlin | year = 1938 | pages = 77–85}}.</ref> The succinct expression as the 4''n''+2 rule has been attributed to von Doering (1951),<ref>{{citation | last = Doering | first = W. v. E. | series = Abstracts of the American Chemical Society Meeting, New York | date = September 1951 | page = 24M}}.</ref> although several authors were using this form at around the same time.<ref>See Roberts et al. (1952) and refs. therein.</ref> |

|||

A [[Cyclic compound|cyclic]] ring molecule follows Hückel's rule when the number of its [[pi electron|π-electron]]s equals 4''n''+2 where ''n'' is zero or any positive [[integer]], although clearcut examples are really only established for values of ''n'' = 0 up to about ''n'' = 6.<ref>{{March3rd}}</ref> Hückel's rule was originally based on calculations using the [[Hückel method]], although it can also be justified by considering a [[particle in a ring]] system, by the [[Linear combination of atomic orbitals molecular orbital method|LCAO method]]<ref name="Roberts">{{citation | first1 = John D. | last1 = Roberts | first2 = Andrew, Jr. | last2 = Streitweiser | first3 = Clare M. | last3 = Regan | title = Small-Ring Compounds. X. Molecular Orbital Calculations of Properties of Some Small-Ring Hydrocarbons and Free Radicals | journal = J. Am. Chem. Soc. | year = 1952 | volume = 74 | issue = 18 | pages = 4579–82 | doi = 10.1021/ja01138a038}}.</ref> and by the [[Pariser–Parr–Pople method]]. |

|||

Aromatic compounds are more stable than theoretically predicted by alkene hydrogenation data; the "extra" stability is due to the delocalized cloud of electrons, called resonance energy. Criteria for simple aromatics are: |

|||

#follow Huckel's rule, having 4''n''+2 electrons in the delocalized cloud; |

|||

#be able to be planar and are cyclic; |

|||

#every atom in the circle is able to participate in delocalizing the electrons by having a p-orbital or an unshared pair of electrons. |

|||

==Refinement== |

|||

Hückel's rule is not valid for many compounds containing more than three fused aromatic nuclei in a cyclic fashion. For example, [[pyrene]] contains 16 conjugated electrons (8 bonds), and [[coronene]] contains 24 conjugated electrons (12 bonds). Both of these polycyclic molecules are aromatic even though they fail the 4''n''+2 rule. Indeed, Hückel's rule can only be theoretically justified for monocyclic systems.<ref name="Roberts"/> |

|||

==Three-dimensional rule== |

|||

In 2000, Andreas Hirsch and coworkers in [[Erlangen]], [[Germany]], formulated a rule to determine when a [[fullerene]] would be aromatic. In particular, they found that, if there were 2(''n''+1)<sup>2</sup> π-[[electrons]], then the fullerene would display aromatic properties. This follows from the fact that an aromatic fullerene must have full [[icosahedral]] (or other appropriate) symmetry, so the molecular orbitals must be entirely filled. This is possible only if there are exactly 2(''n''+1)<sup>2</sup> electrons, where ''n'' is a nonnegative integer. In particular, for example, [[buckminsterfullerene]], with 60 π-electrons, is non-aromatic, since 60/2 = 30, which is not a [[perfect square]].<ref>{{citation | title = Spherical Aromaticity in ''I''<sub>h</sub> Symmetrical Fullerenes: The 2(''N''+1)<sup>2</sup> Rule | pages = 3915–17 | first1 = Andreas | last1 = Hirsch | first2 = Zhongfang | last2 = Chen | first3 = Haijun | last3 = Jiao | journal = Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. | year = 2000 | volume = 39 | issue = 21 | doi = 10.1002/1521-3773(20001103)39:21<3915::AID-ANIE3915>3.0.CO;2-O}}.</ref> |

|||

== Characteristics of aromatic (Aryl) compounds == |

== Characteristics of aromatic (Aryl) compounds == |

||

Versiunea de la 15 noiembrie 2009 12:25

| Unul sau mai mulți editori lucrează în prezent la această pagină sau secțiune. Pentru a evita conflictele de editare și alte confuzii creatorul solicită ca, pentru o perioadă scurtă de timp, această pagină să nu fie editată inutil sau nominalizată pentru ștergere în această etapă incipientă de dezvoltare, chiar dacă există unele lacune de conținut. Dacă observați că nu au mai avut loc modificări de 10 zile puteți șterge această etichetă. |

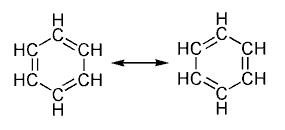

În urma a numeroase experimente s-a constatat că majoritatea structurilor ciclice au o stabilitate foarte mare.Acest lucru se datorează caracterului aromatic, caracter ce este explicat prin prezenţa sistemelor conjugate, a electronilor de valenţă liberi, sau a orbitalilor liberi fapt ce conduce la o mai mare stabilitate faţă de cea aşteptată prin simpla conjugare.Caracterul aromatic poate fi considerat şi o consecinţă a delocalizării ciclice şi a rezonanţei. [1][2][3] Aceasta se explică pri faptul că electronii liberi au o circulaţie liberă la nivelul aranjamentului de tip circular care este adoptat de atomi, strcutură circulară în care alternează simplee ţi dublele legături.Aceste legături sunt identice între ele, acest model fiind foarte asemănător cu cel al benzenului propus de Kekulé.Acesta a propus pentru benzen 2 formule de rezonanţă care corespund alternării dublelor şi a simplelor legături 1,3,5 ciclohexatrienică.Contrar acestei structuri benzenul este mult mai stabil, mai ales termic.

Teorii

Teoria rezonanţei

Formulele de rezonanţă se indică prin săgeată dublu sens, tocmai pentru a arăta ca structurile rezonantice nu sunt compuşi diferiţi ci mai mult ipotetici.prins cristalografie în raze s-a constatat ca legăturile simple C-C sau valoare de 140 pm mai mari faţa de legăturile C=C (valoare 1.35m ) dar mai mici faţă de legăturile C-C simple din alcani 147pm.Teoretic legătura dublă ar deformat structura planară a benzenului, lucru contrazis de structura perfect plan hexagonală a benzenului.Acest fapt dovedeşte toate 6 legături C-C au aceeaşi lungime şi au o valoare intermediară intre valoarea unei duble legături şi a uneia simple.

Teoria orbitalilor

O reprezentare mai exactă este cea circulară a orbitalilor π (inelul sau ciclul Armstrong), în care densitatea electronică este distribuită în mod uniform deasupra şi dedesubtul planului moleculei.prin acest model se reprezintă mult mai bine localizarea electronică.Se explică astfel şi stabilitatea nucleului benzenic şi echivalenţa legăturilor C-C care se datorează delocalizării celor 6 electroni π, dar şi a distribuiiri lor uniforme pe suprafaţa ciclului.Legăturile simple sunt de tip σm, în timp ce legăturile duble au la bază σ şi π.

Datorită distribuirii uniforme a electronilor neparticipanţi pe întreg ciclul aromatic, cei 6 orbitali π nehibridizaţi vor fuziona dînd naştere la un orbital molecular extins.

Istoric

S-a observat că prin degradarea a diferiţi compuşi plăcut mirositori se obţineau molecule cu schelet format din 6 atomi de carbon.Prima utilizare a cuvântului aromatic este facută de către August Wilhelm Hofmann într-un articol apărut în 1855.[4].Curios este că la acea vreme singurele substanţe "aromatice" (puternic aromatice)erau terpenele, care în sens strict chimic nu sunt compuşi aromatici.Asemănarea dintre aceste 2 clase de substanţe este dat gradul mare de nesaturare consecinţa numărului de duble legături.La acea vreme însă Hofman nu putea face distincţia între cele 2 clase de compuşi.

Formula Kekulé

Elaborată pentru prima dată de August Kekulé în 1865, ţine cont de formula moleculară a benzenului, de valenţele atomilor de carbon şi hidrogen astfel încât acesta atribuie benzenului o formulă 1,3,5 ciclohexatrienică.Aceasta fomrulă a fost mult timp unanim acceptată deoarece era în concordanţă cu izomeria şi cvu om parte a reacţiilor chimice datorate acestei structuri.Însă pe parcursul timpului au foist observate anumite comportări chimice în dezacord cu această structură:

- Suferă mai uşor reacţii de substituţie decât de polimerizare şi adiţie

- Se degradează (oxidează) numai în condiţii energice

- Prin oxidarea omologilor rezultă întotdeauna acid benzoic ceea ce demonstrează stabilitatea nucleului comparativ cu catena laterală.

- Reacţiile de adiţie ale hidrogenului, halogenilor au loc doar în condiţii energice.

Teoria sextetului

Decsoperirea electronului de către J. J. Thomson, 1897-1906, a dus la o îmbunătăţire a teoriei privind structura benezenului, prin alocarea fiecărui atom de carbon a unui electron.

O posibilă explicaţie referitoare la stabiolitatea foarte mare e benzenului este oferită de Robert Robinsoncare în anul 1925[5] defineşte pentru prima oară denumirea de sextet aromatic , un grup de 6 electroni ce conferă stabilitaea ciclului aromatic.Conceptul de sextet aromatic este însă introdus în anul 1922 de Ernest Crocker în 1922,[6] iar înaintea lui de Henry Edward Armstrong, care în anul 1890, într-un articol intitulat The structure of cycloid hydrocarbons (Structura cicloidă a hidrocarburilor) , arată : the (six) centric affinities act within a cycle...benzene may be represented by a double ring (sic) ... and when an additive compound is formed, the inner cycle of affinity suffers disruption, the contiguous carbon-atoms to which nothing has been attached of necessity acquire the ethylenic condition "cei şase centri ai afinităţii acţionează în interiorul unui inel...benzenul poate fi reprezentat prin două inele duble (sic) iar când are loc formarea unui compus prin adiţie inelul interior al afinităţii este distrus, atomii de carbon vecini liberi vor trece în starea etilenică".[7] Armstrong anticipează astfel cel puţin 4 concepte moderne.Primul este afinitatea de fapt electronul de mai târziu descoperit de J. J. Thomson.Al doilea concept este descrierea substituţiei electrofile prin intermediarul de tip Wheland (ion benzenoniu)(concept 3) , proces ce are loc cu distrugerea sistemului conjugat al inelului aromatic (al 4-lea concept).El introduce simbolul C centrat în mijlocul inelului interior , anticipând astfel notarea Eric Clar.Prin aceasta se anticipează principiile mecanicii cuantice , de vreme ce recunoaşte că afinităţile(electronii) au aceeeaşi orientare, nu sunt punctiforme la nivel de atom, au o distribuţie uniformă ce poate fi alterată prin introducerea uneo substituenţi pe nucleul aromatic.

Condiţii de apariţie a stării aromatice

Prin intermediul mecanicii cuanticeHückel explică stabilitatea , caracterul aromatic, separînd pentru prima dată electronii de legătură în electroni sigma şi electroni pi.

Regula HückelText de titlu

In organic chemistry, 's rule estimates whether a planar ring molecule will have aromatic properties. The quantum mechanical basis for its formulation was first worked out by physical chemist Erich Hückel in 1931.[8][9] The succinct expression as the 4n+2 rule has been attributed to von Doering (1951),[10] although several authors were using this form at around the same time.[11]

A cyclic ring molecule follows Hückel's rule when the number of its π-electrons equals 4n+2 where n is zero or any positive integer, although clearcut examples are really only established for values of n = 0 up to about n = 6.[12] Hückel's rule was originally based on calculations using the Hückel method, although it can also be justified by considering a particle in a ring system, by the LCAO method[13] and by the Pariser–Parr–Pople method.

Aromatic compounds are more stable than theoretically predicted by alkene hydrogenation data; the "extra" stability is due to the delocalized cloud of electrons, called resonance energy. Criteria for simple aromatics are:

- follow Huckel's rule, having 4n+2 electrons in the delocalized cloud;

- be able to be planar and are cyclic;

- every atom in the circle is able to participate in delocalizing the electrons by having a p-orbital or an unshared pair of electrons.

Refinement

Hückel's rule is not valid for many compounds containing more than three fused aromatic nuclei in a cyclic fashion. For example, pyrene contains 16 conjugated electrons (8 bonds), and coronene contains 24 conjugated electrons (12 bonds). Both of these polycyclic molecules are aromatic even though they fail the 4n+2 rule. Indeed, Hückel's rule can only be theoretically justified for monocyclic systems.[13]

Three-dimensional rule

In 2000, Andreas Hirsch and coworkers in Erlangen, Germany, formulated a rule to determine when a fullerene would be aromatic. In particular, they found that, if there were 2(n+1)2 π-electrons, then the fullerene would display aromatic properties. This follows from the fact that an aromatic fullerene must have full icosahedral (or other appropriate) symmetry, so the molecular orbitals must be entirely filled. This is possible only if there are exactly 2(n+1)2 electrons, where n is a nonnegative integer. In particular, for example, buckminsterfullerene, with 60 π-electrons, is non-aromatic, since 60/2 = 30, which is not a perfect square.[14]

Characteristics of aromatic (Aryl) compounds

An aromatic compound contains a set of covalently-bound atoms with specific characteristics:

- A delocalized conjugated π system, most commonly an arrangement of alternating single and double bonds

- Coplanar structure, with all the contributing atoms in the same plane

- Contributing atoms arranged in one or more rings

- A number of π delocalized electrons that is even, but not a multiple of 4. That is, 4n + 2 number of π electrons, where n=0, 1, 2, 3, and so on. This is known as Hückel's Rule.

Whereas benzene is aromatic (6 electrons, from 3 double bonds), cyclobutadiene is not, since the number of π delocalized electrons is 4, which of course is a multiple of 4. The cyclobutadienide (2−) ion, however, is aromatic (6 electrons). An atom in an aromatic system can have other electrons that are not part of the system, and are therefore ignored for the 4n + 2 rule. In furan, the oxygen atom is sp² hybridized. One lone pair is in the π system and the other in the plane of the ring (analogous to C-H bond on the other positions). There are 6 π electrons, so furan is aromatic.

Aromatic molecules typically display enhanced chemical stability, compared to similar non-aromatic molecules. A molecule that can be aromatic will tend to alter its electronic or conformational structure to be in this situation. This extra stability changes the chemistry of the molecule. Aromatic compounds undergo electrophilic aromatic substitution and nucleophilic aromatic substitution reactions, but not electrophilic addition reactions as happens with carbon-carbon double bonds.

Many of the earliest-known examples of aromatic compounds, such as benzene and toluene, have distinctive pleasant smells. This property led to the term "aromatic" for this class of compounds, and hence the term "aromaticity" for the eventually-discovered electronic property.

The circulating π electrons in an aromatic molecule produce ring currents that oppose the applied magnetic field in NMR. The NMR signal of protons in the plane of an aromatic ring are shifted substantially further down-field than those on non-aromatic sp² carbons. This is an important way of detecting aromaticity. By the same mechanism, the signals of protons located near the ring axis are shifted up-field.

Aromatic molecules are able to interact with each other in so-called π-π stacking: the π systems form two parallel rings overlap in a "face-to-face" orientation. Aromatic molecules are also able to interact with each other in an "edge-to-face" orientation: the slight positive charge of the substituents on the ring atoms of one molecule are attracted to the slight negative charge of the aromatic system on another molecule.

Planar monocyclic molecules containing 4n π electrons are called antiaromatic and are, in general, destabilized. Molecules that could be antiaromatic will tend to alter their electronic or conformational structure to avoid this situation, thereby becoming non-aromatic. For example, cyclooctatetraene (COT) distorts itself out of planarity, breaking π overlap between adjacent double bonds. Relatively recently, cyclobutadiene was discovered to adopt an asymmetric, rectangular configuration in which single and double bonds indeed alternate; there is no resonance and the single bonds are markedly longer than the double bonds, reducing unfavorable p-orbital overlap. Hence, cyclobutadiene is non-aromatic; the strain of the asymmetric configuration outweighs the anti-aromatic destabilization that would afflict the symmetric, square configuration.

Importance of aromatic compounds

Aromatic compounds are important in industry. Key aromatic hydrocarbons of commercial interest are benzene, toluene, ortho-xylene and para-xylene. About 35 million tonnes are produced worldwide every year. They are extracted from complex mixtures obtained by the refining of oil or by distillation of coal tar, and are used to produce a range of important chemicals and polymers, including styrene, phenol, aniline, polyester and nylon.

Other aromatic compounds play key roles in the biochemistry of all living things. Three aromatic amino acids phenylalanine, tryptophan, and tyrosine, each serve as one of the 20 basic building blocks of proteins. Further, all 5 nucleotides (adenine, thymine, cytosine, guanine, and uracil) that make up the sequence of the genetic code in DNA and RNA are aromatic purines or pyrimidines. As well as that, the molecule haem contains an aromatic system with 22 π electrons. Chlorophyll also has a similar aromatic system.

Types of aromatic compounds

The overwhelming majority of aromatic compounds are compounds of carbon, but they need not be hydrocarbons.

Heterocyclics

In heterocyclic aromatics (heteroaromats), one or more of the atoms in the aromatic ring is of an element other than carbon. This can lessen the ring's aromaticity, and thus (as in the case of furan) increase its reactivity. Other examples include pyridine, pyrazine, imidazole, pyrazole, oxazole, thiophene, and their benzannulated analogs (benzimidazole, for example).

Polycyclics

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are molecules containing two or more simple aromatic rings fused together by sharing two neighboring carbon atoms (see also simple aromatic rings). Examples are naphthalene, anthracene and phenanthrene.

Substituted aromatics

Many chemical compounds are aromatic rings with other things attached. Examples include trinitrotoluene (TNT), acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin), paracetamol, and the nucleotides of DNA.

Atypical aromatic compounds

Aromaticity is found in ions as well: the cyclopropenyl cation (2e system), the cyclopentadienyl anion (6e system), the tropylium ion (6e) and the cyclooctatetraene dianion (10e). Aromatic properties have been attributed to non-benzenoid compounds such as tropone. Aromatic properties are tested to the limit in a class of compounds called cyclophanes.

A special case of aromaticity is found in homoaromaticity where conjugation is interrupted by a single sp³ hybridized carbon atom. When carbon in benzene is replaced by other elements in borabenzene, silabenzene, germanabenzene, stannabenzene, phosphorine or pyrylium salts the aromaticity is still retained.

Aromaticity occurs in compounds not made of carbon as well. Inorganic 6 membered ring compounds analogous to benzene have been synthesized. Silicazine (Si6H6) and borazine (B3N3H6) are structurally analogous to benzene, with the carbon atoms replaced by another element or elements. In borazine, the boron and nitrogen atoms alternate around the ring.

Metal aromaticity is believed to exist in certain metal clusters of aluminium. Möbius aromaticity occurs when a cyclic system of molecular orbitals, formed from pπ atomic orbitals and populated in a closed shell by 4n (n is an integer) electrons, is given a single half-twist to correspond to a Möbius strip. Because the twist can be left-handed or right-handed, the resulting Möbius aromatics are dissymmetric or chiral. Up to now there is no doubtless proof that a Möbius aromatic molecule was synthesized.[15][16] Aromatics with two half-twists corresponding to the paradromic topologies, first suggested by Johann Listing, have been proposed by Rzepa in 2005.[17] In carbo-benzene the ring bonds are extended with alkyne and allene groups.

References

- ^ P. v. R. Schleyer, "Aromaticity (Editorial)", Chemical Reviews, 2001, 101, 1115-1118. DOI: 10.1021/cr0103221 Abstract.

- ^ A. T. Balaban, P. v. R. Schleyer and H. S. Rzepa, "Crocker, Not Armit and Robinson, Begat the Six Aromatic Electrons", Chemical Reviews, 2005, 105, 3436-3447. DOI: 10.1021/cr0103221 Abstract.

- ^ P. v. R. Schleyer, "Introduction: Delocalization-π and σ (Editorial)", Chemical Reviews, 2005, 105, 3433-3435. DOI: 10.1021/cr030095y Abstract.

- ^ A. W. Hofmann, "On Insolinic Acid," Proceedings of the Royal Society, 8 (1855), 1-3.

- ^ "CCXI.—Polynuclear heterocyclic aromatic types. Part II. Some anhydronium bases" James Wilson Armit and Robert Robinson Journal of the Chemical Society, Transactions, 1925, 127, 1604–1618 Abstract.

- ^ APPLICATION OF THE OCTET THEORY TO SINGLE-RING AROMATIC COMPOUNDS Ernest C. Crocker J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1922; 44(8) pp 1618–1630; Abstract

- ^ The structure of cycloid hydrocarbons Henry Edward Armstrong Proceedings of the Chemical Society (London), 1890, 6, 95 - 106 Abstract

- ^ Hückel, Erich (), „Quantentheoretische Beiträge zum Benzolproblem I. Die Elektronenkonfiguration des Benzols und verwandter Verbindungen”, Z. Phys., 70 (3/4): 204–86, doi:10.1007/BF01339530. Hückel, Erich (), „Quanstentheoretische Beiträge zum Benzolproblem II. Quantentheorie der induzierten Polaritäten”, Z. Phys., 72 (5/6): 310–37, doi:10.1007/BF01341953. Hückel, Erich (), „Quantentheoretische Beiträge zum Problem der aromatischen und ungesättigten Verbindungen. III”, Z. Phys., 76 (9/10): 628–48, doi:10.1007/BF01341936.

- ^ Hückel, E. (), Grundzüge der Theorie ungesättiger und aromatischer Verbindungen, Berlin: Verlag Chem, pp. 77–85.

- ^ Doering, W. v. E. (septembrie 1951), Abstracts of the American Chemical Society Meeting, New York, p. 24M Lipsește sau este vid:

|title=(ajutor). - ^ See Roberts et al. (1952) and refs. therein.

- ^ Format:March3rd

- ^ a b Roberts, John D.; Streitweiser, Andrew, Jr.; Regan, Clare M. (), „Small-Ring Compounds. X. Molecular Orbital Calculations of Properties of Some Small-Ring Hydrocarbons and Free Radicals”, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 74 (18): 4579–82, doi:10.1021/ja01138a038.

- ^ Hirsch, Andreas; Chen, Zhongfang; Jiao, Haijun (), „Spherical Aromaticity in Ih Symmetrical Fullerenes: The 2(N+1)2 Rule”, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl., 39 (21): 3915–17, doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20001103)39:21<3915::AID-ANIE3915>3.0.CO;2-O.

- ^ Synthesis of a Möbius aromatic hydrocarbon D. Ajami, O. Oeckler, A. Simon, R. Herges, Nature; 2003; 426 pp 819.

- ^ Investigation of a Putative Möbius Aromatic Hydrocarbon. The Effect of Benzannelation on Möbius [4 n]Annulene Aromaticity Claire Castro, Zhongfang Chen, Chaitanya S. Wannere, Haijun Jiao, William L. Karney, Michael Mauksch, Ralph Puchta, Nico J. R. van Eikema Hommes, Paul von R. Schleyer J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 2005; 127(8) pp 2425-2432 Abstract

- ^ A Double-Twist Möbius-Aromatic Conformation of [14]Annulene Henry S. Rzepa Org. Lett.; 2005; 7(21) pp 4637 Abstract